Netscape, SOX and the Price of Housing

Between the terrible events of 11 September 2001 and the financial crisis of 2008, US - and eventually global - housing prices rose to absurdly high levels. It is interesting how quickly people become used to high prices as "natural;" when I was selling property in 2009 in a bad market, just about everyone advised me to wait it out until prices returned to "their natural levels." For some reason, housing prices of 50% higher than their long-term average against income are considered more "natural", even though they had been that way over a very short span of time, versus their, well, long-term average!

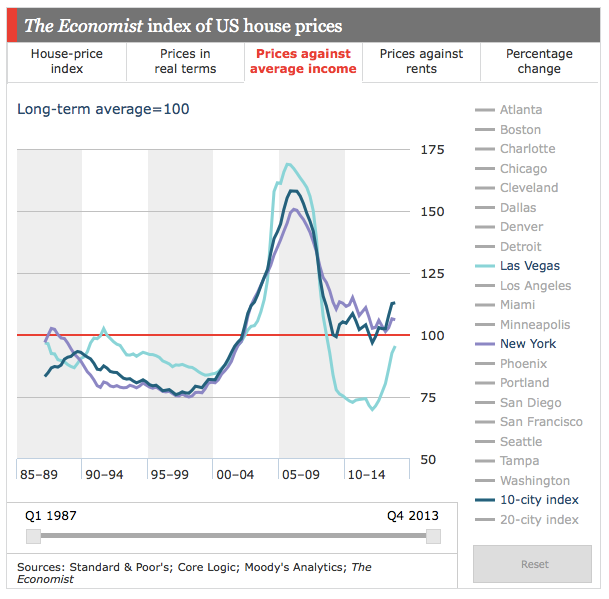

The following graph, courtesy of the Economist and available in interactive format here, shows US housing prices vs average income.

As can be seen very clearly, for some reason, from around 2002 until 2008, housing prices rose dramatically as compared to income, as well as in real terms. A question that has vexed me for quite some time is, why? There are a lot of potential answers, and the Fed's pumping of money into the economy was always part of the answer. But a few days ago I read an interview with Marc Andreessen explaining why "the IPO is dying." As Marc explained it, a mix of factors, but especially the heavy burdens of Sarbanes-Oxley (or "SOX"), have made it very difficult for smaller companies to go public. Since the costs of SOX are largely fixed at millions of dollars per year, you are far less likely to go IPO until your operating margin is much much larger, and you can absorb the SOX costs better.

For example, a $100MM revenue tech company that is growing quickly but only has an 8% operating margin (it is growing, after all), only has $8MM in free cash to play with. If SOX costs $4MM, they have just lost half their profit! On the other hand, a $4BN revenue company, even if it only has 10% in operating margin, has $400MM to play with. Even if SOX costs are double those of the smaller company - they do not rise linearly with company size - it only hurt their profits by 2%.

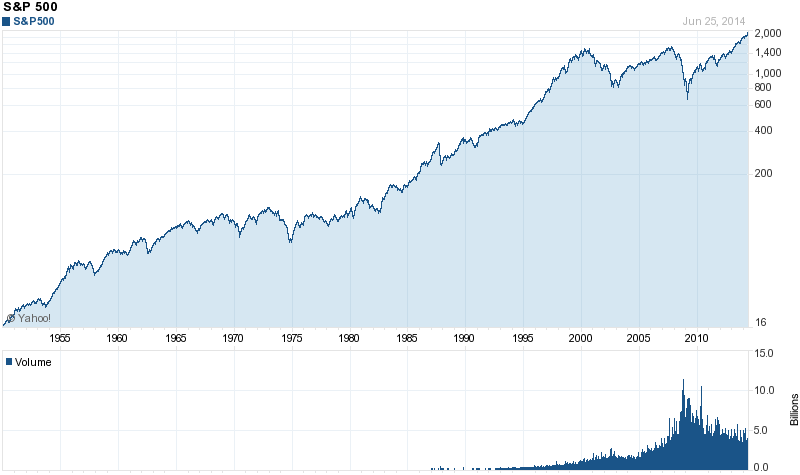

I think Marc missed a few other elements, especially litigation costs, but the lack of IPOs until much of a company's rocket growth is well past it, means that equity markets provide much lower returns than they used to. As Marc points out, over the long term, the S&P500 - the broad market - provided 6 to 7 percent annual returns. With compounding, that can be great, even accounting for inflation. But in the nearly 15 years since 2000, the S&P500 has been flat to down. There have been short periods of growth, but those are really just recoveries from troughs. Look at the following graph, courtesy of Yahoo Finance:

Basically, if you put $1,000 into the S&P500 in 2000, today it would be worth about... $1,000. Once you account for inflation - $1,000 in 2000 is worth $1,382 in 2014 - you have actually lost a lot of money!

When it comes down to it, most people have only one of three places to invest their money:

- Equity

- Debt

- Real estate

Sure, some can invest in gold or other commodities, but large-scale investment happens in those three. Beginning in 2000, SOX made real equity returns were negative, the Fed made real interest rates were negative, and there was a lot of cash waiting to be invested somewhere. Inevitably, the money ended up in real estate, itself a limited commodity. With all of those funds pumping in, prices were bound to rise, a bubble form... and eventually pop.

SOX + negative interest rates = Housing bubble