Do VCs Abandon Startups?

For years, people I have known in the VC business, as well as entrepreneurs who have been funded by VCs, have discussed the 7-2-1 rule.

For every 10 investments a VC fund makes:

- 7 will fail - "dogs"

- 2 will hang around, perhaps returning the initial investment - "zombies"

- 1 will be a great success - "superstar"

This formula is why VCs are willing to take such risks; they expect many companies in their portfolio to fail. Sure, they would prefer if every company were a star, but they don't get emotional about it.

Years ago, a friend of mine from IT at a major investment bank went to Silicon Valley to work in the company's venture financing arm. After a year or so, we discussed how to fix the "dogs". His response? Don't bother. Once a company is recognized as a dog, the VCs do not want to put in the blood and treasure to try and fix it. They are in the business of building new growing companies, not saving failed ones.

This, of course, is the source of the VC version of the "agency problem": misaligned incentives. An investor views each company as one among several in its portfolio, like one of ten stocks in your portfolio. You may want them all to go up, but you put the effort where you expect the most return. The entrepreneur, on the other hand, has one big investment: his or her company. The entrepreneur does not care what else is in the investor's portfolio; he or she will do everything to make this investment succeed.

Today, I received a completely different perspective from one of my favourite VC writers, Mark Suster. Mark discussed the two different paths to tech company CEO. The first is to have been one in the past, usually through founding a company. However, if you never were one, and cannot take on the risk of starting your own due to your later stage and higher fiscal responsibilities in life - try living off Ramen noodles when you have a mortgage and three kids to feed, clothe and educate - you may the experience to fix a failing firm. This task has a different set of requirements than those for a fast-growing startup.

The conflict is obvious. If a VC normally writes off the dogs, why would a VC hire an executive team, and invest another chunk of change, to turn around the firm? How do you reconcile 7-2-1 with the turnaround?

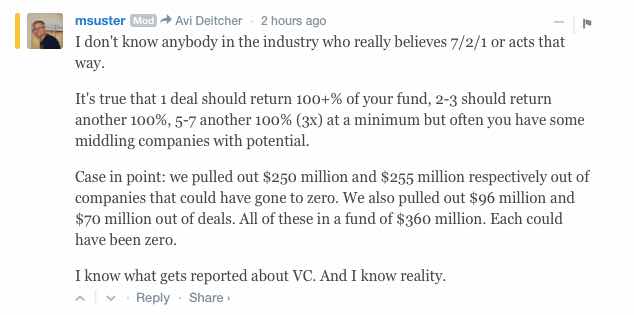

I asked exactly that question. Mark's answer is worth repeating in its entirety:

So is 7-2-1 a myth? I don't believe so. I do not have anywhere near the connections or experience in the VC industry that Mark Suster does, but I have heard it, or some variant, from too many investors and entrepreneurs in the US, Canada, Israel and Britain.

The answer, I think, lies in two different directions: plans vs. effort and types of investors.

Plans vs. Reality

Every entrepreneur falls prey to over-optimism. The entrepreneur believes customer acquisition costs (CAC) will be lower, lifetime value (LTV) will be higher, sales cycles will be shorter, market share will be greater, etc. It is part and parcel of the optimistic nature necessary to become an entrepreneur.

The antidote to over-optimism is hard numbers and cold reality. An entrepreneur needs to see what CAC really costs in his or her industry, what LTV really maxes out at, how long sales really take.

Venture capitalists are entrepreneurs as well. Instead of selling stock in their company to venture investors, they sell investments in their funds to limited partners; instead of selling a vision of 3x or 5x or 20x return on an early-stage investment in their company, they sell 10% or 15% or 30% annual returns in their fund.

VCs are equally likely to fall prey to over-optimism. The counter-balance to the belief that "every investment I pick will be a star" is 7-2-1. If you can make your returns expecting 7-2-1, then everything else is icing on the cake, and makes you a better investor and future bet for your limited partners.

In reality, of course, every good entrepreneur who expected 6 month sales cycles should work to cut them down to 5 months, then 4, then 3. Every great SaaS CEO who expected 3% annual churn should labour mightily to get down to 2.5% or 2% or lower.

Similarly, every VC worth his or her salt should struggle to make each company successful, even if it will never be a superstar. Make the zombies positive exits, make the dogs reasonably successful.

There is, however, a deeper element at play.

Type of VC

Not all VCs are the same. Some are just finance types, who have never been on the operational side of the business, never managed real people with real pain, never struggled to make payroll. These are the people who will always look at their portfolio as just cold, hard numbers. When a company starts to look like it is part of the 7, rather than the 2 or 1, why waste time? Sell the stock, cut your losses, walk away.

Other VCs have been on the operational side. They view each company as one of their children, each founder and CEO as one of their family. Yes, if they have to, when there is nothing left to do, they will cut their losses and walk. But they will do everything possible to turn the company around first, and when they cut their losses, they do it with a heavy heart, because they have been there.

Every company goes through hard times, startups more than most, especially early on. I suspect that companies in portfolios shift around over time as being one of the winners or one of the losers.

It is great, even necessary, as a founder to be optimistic. Cold, hard numbers show you the potential downsides, help you be aware of when you are going through rough times, and help you manage them. When those times come, wouldn't you want an investor on your team who will do everything to bring your company to positive value?

I know I would.