HP Printing Is An Ink Company, Not a Printer Company

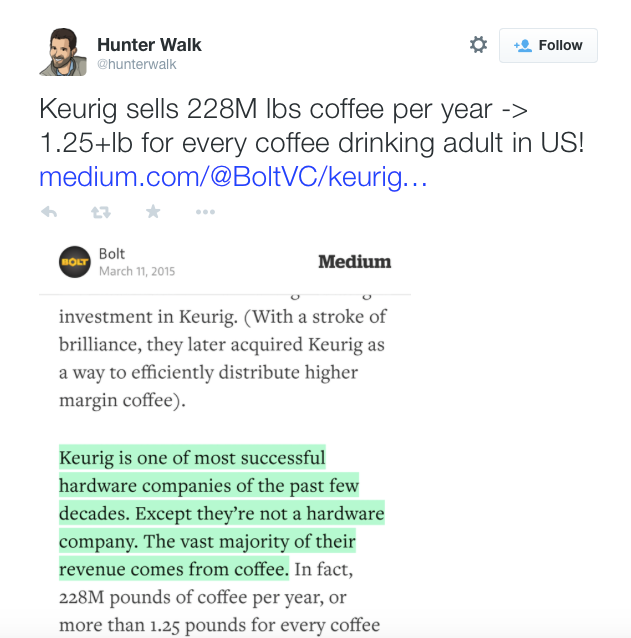

Late last night, Hunter Walk, of HomeBrew Seed Stage VC, tweeted out the following:

This shouldn't be too surprising; people and businesses buy the machine once, but the K-Cup refills are bought over and over again. This is why Keurig has been so intent on keeping machine users buying their coffee, by any means necessary.

A year ago, I wrote how I found a mention in their annual report about digital rights management (DRM) to force Keurig machines to accept only "genuine" K-Cups, and how I expected it to backfire, based on: my own experience; competitive markets; and research from my own Duke professors on piracy and DRM. More recently, I followed it up with Keurig's actual implementation of DRM, how customers are bypassing it, and how Keurig is doomed to difficulty if it chooses to fight its customers rather than work with them.

There is an interesting and parallel lesson from HP.

HP recently reorganized into 2 approximately equally-sized business units:

- Hewlett-Packard Enterprise, which sells software, services, hardware and consulting to large enterprises, 2014 revenue of $57.6BN

- HP Inc., which sells personal systems, such as PCs, and printers, 2014 revenue of $57,3BN

HP Inc. Printing Division (let's call it "HPP"), accounted for about 40% of HP Inc. revenues. Let's look at the revenues of HP, the printer company.

The details for HPP are listed on page 62 of HP's 10K annual report, available here. They list three parts of the business:

- Supplies: replacement toners and ink

- Consumer Hardware: your DeskJet printer

- Commercial Hardware: your OfficeJet Pro and LaserJet

Total HPP revenues in FY2014 were $22,979MM.

Unfortunately, HP does not break out the balance of revenue between Supplies, Consumer and Commercial within HPP. Fortunately, with a little math, we can back into them... and wonder why they didn't break them out!

HPP revenue declined from FY2013 to FY2014 by 3.8%, or $917MM. While HP does not report revenues for each section of HPP, it does report the change in each. The 3.8% decline was composed of:

- Supplies: 3.3%

- Consumer: 0.4%

- Commercial: 0.1%

If 3.3% out of the 3.8% decline was in Supplies. (3.3/3.8)*$917MM = $796MM. HP also tells us that "Net revenue for Supplies decreased 5% driven by demand weakness in toner and ink." The $796MM decline in Supplies represents 5% of previous year's revenues. So FY2013 Supplies revenues were $796MM/.05 = $15,920MM, and FY2014 revenues were $15,920 - $796 = $15,124MM. Now, with total HPP revenues in hand, we can determine the percentage of HPP revenue that comes from Supplies:

- FY2013: Supplies = $15,920MM, HPP = $23,896MM, Supplies/HPP = 66.6%

- FY2014: Supplies = $15,124MM, HPP = $22,979MM, Supplies/HPP = 65.8%

In the last two years, HPP Supplies were approximately 2/3 of HPP Revenue. For all intents and purposes, HPP is a printing supplies company.

However, because it uses printer hardware to drive ink and toner sales, it is susceptible to swings in its Supplies market, as occurred last year. Of the $917MM drop in HPP revenue, $796MM = 89.5% of the drop was because of weak demand for supplies.

Finally, while HPP had a more favourable 2014 in terms of profit, as earnings from operations increased on an absolute basis from $3.9BN to $4.2BN, in the face of a revenue decline that caused its operating margins to increase from 16.5% to 18.2%, HP admits that this was primarily due to foreign currency (JPY) effects and "cost structure improvements" - which could mean better processes or it could mean layoffs to boost the bottom line, which is not sustainable in the long run. They state outright several times that HPP faces a "competitive pricing environment."

It is interesting to note, briefly, that the previous year HPP revenues declined 2.6%, while Supplies revenue declined by 3%. Not only was the entire decline was due to Supplies, but it even knocked out some modest gains in other parts of HPP.

What does this all mean?

- HPP is a printing supplies company far more than a printer hardware company.

- HPP has gotten used to charging a premium for its printing products while selling printers relatively cheaply. While not quite a loss-leader strategy, they has been willing to accept lower margins on hardware while expecting to lock in the customer on supplies for the 2-3 year printer lifespan.

- HPP is suffering a decline in its business, which, because of its outsized dependency on Supplies, is accelerating.

- HPP is facing a "competitive pricing environment", as third-party printer-supply suppliers offer good substitutions at half to two-thirds the price.

- Many customers no longer feel bound to buy HP supplies to feed their HP printers, especially as they come out of warranty.

Is HPP facing an existential risk? Hard to tell. It will, however, have to think hard about whether or not to retool itself to face the competitive onslaught. I would consider several steps:

- Accept that ink and toner have become commodity, and structure the Supplies business around "Original HP" products that sell at a small (15-25%) brand premium over generics.

- Eliminate DRM restrictions in HP printers. Let customers know that an HP printer is a great printer, for a price. With HP supplies, you get a warranty, and they only cost a bit more than "that second-tier garbage," but it will work with whatever you put in it.

- Offer free extended warranties to any printer that never has anything but original HP ink in it. Instead of DRM preventing alternate ink supplies, let it just track alternate supplies. Stop thinking about supplies as supplies; start thinking about them as service.

- Expand the Brand. Sell original HP ink and toner that are compatible with other printers. Turn HP Supplies into great quality supplies for every printer.

Summary

Any business that sells for lower-cost upfront while expecting to capture recurring revenues over time, like HP and Keurig, needs to have a compelling offer to entice the customer to keep coming back.

This is exactly the issue in SaaS, where you need a sufficiently high Customer Lifetime Value (LTV or CLTV) to compensate for the upfront Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

If you lock your customer in such that they want to leave but feel they cannot, eventually they will force their way out and you will face an unrecoverable death spiral. By contrast, if you continually make it compelling, and expand the benefits beyond the original customer set, you will face lower recurring revenues per customer per month, but customers with lower churn, leading to a longer lifecycle and a higher LTV.

Do you know if your customers are sticking with you because they want to, or because they fell trapped? Is your future Salesforce.com or HPP? And what will HPP do to fix it?