You Are What You Sell

At the risk of kicking someone when they are down, let's look at... GoPro.

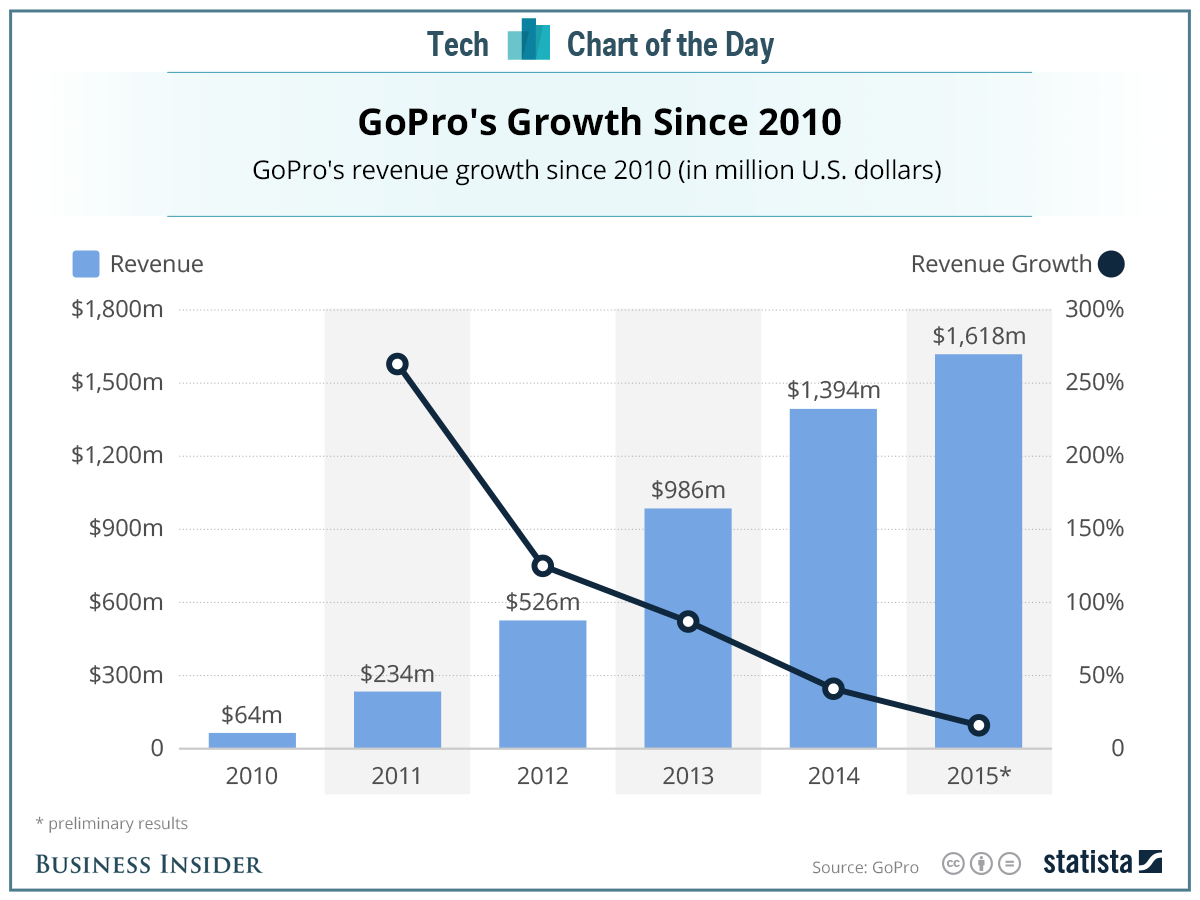

GoPro recently reported slower than anticipated sales, laid off 7% of their staff, and had their stock hammered (down 14.5% in a day). BusinessInsider did a straightforward if nice job showing their absolute revenue and relative year-over-year growth for the last 5 years. While total sales numbers are nice, the growth numbers aren't pretty.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="1200"] GoPro revenue and growth[/caption]

GoPro revenue and growth[/caption]

My favourite quote is from Marc Andreessen, responding to Chris Dixon:

https://twitter.com/pmarca/status/432038518995447809?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

GoPro believed (made themselves believe?) that they were not "just" a hardware company, but really a sports enthusiast community that "happens" to monetize via electronics; as @pmarca said, that is a "convenient fiction."

At heart, every company needs to believe there is something about their business model that is unique, special, has a "magic sauce" that will keep customers coming back. GoPro executives had to believe they were "more than just a hardware company", because if not, commoditization was inevitable.

While it is pretty clear to everyone what happened, a more interesting question is what they could have done to prevent - or at least mitigate - the problems.

In the last few days, I have heard a few interesting ideas. Here are two of them.

Leverage Data

A very smart friend of mine who has been doing marketing in the tech sector for many years believes that, like a consultant inside a company who should know where his or her next opportunity lies, GoPro had its own "Internet of Things", or IoT, with millions of devices. It could, it should have found a way to leverage either the devices, the photos/videos or the metadata from them to do one or both of:

- Create alternative revenue streams

- Increase platform value to owners

In theory, GoPro could have used some proprietary photo or video format to lock past use to future use. In practice, customers rebel against it. Andreessen mentioned Flip as an example of what happens to hardware that gets commoditized. I believe that while smartphone video recorders were the primary reason for Flip's collapse, the format lock-in and difficulty in extracting and using Flip-generated video played a significant, if secondary, role.

While they could not lock customers in via formats - "negative lock-in" - they could and should have leveraged the size of the platform to turn it into a real platform, generating additional value - "positive lock-in".

Expand the Market

The other approach would have been to beat back commoditization by commoditizing itself. GoPro is not just one market, but actually 2 (or more). Each requires its own strategy.

On the high end are GoPro's traditional customers, "sports enthusiasts" to use Chris Dixon's term above, who are ready, willing and able to fork over $300-400 for a camera, plus another $50-100 for accessories.

True, real sports enthusiasts shell out good money for the activity they love. I prefer not to think how much I have spent on hockey equipment, training sessions, tournaments and ice time for my children and me. Someone who loves mountain biking and is willing to plunk down $2,000+ in a single moment for a mountain bike is likely to consider spending another few hundred dollars on a high-end camera to capture the moments.

These people - or at least many of them - are looking for the camera with the best quality, best protection, best warranty. They want to know that they can take it scuba diving, parachute jumping or onto the hockey rink and have it work again and again, and they are willing to pay for that privilege.

Nonetheless, costs do come down, and the same $300 item that costs $150 to make today (GoPro's gross margin is ~50%) will cost $100 to make in a few years at the same level of quality. When your margins are now 66%, someone else will come in, manufacture for $100, sell for $150, happily accept 33% margins, and undercut your price by 50%.

Some subset of your current customers will continue to pay a premium for your quality and the brand behind it, but you cannot assume anything close to 100% will.

Look at the cloud. Amazon Web Services (AWS) remains the biggest player on the block, with the greatest diversity of offerings, and yet they continue to reduce prices every chance they get. That continual drop in prices is a major factor in many firms' public-vs-private calculation.

To keep the enthusiast customers, GoPro needed to reduce prices - while keeping margins - as time went on.

Second, there is the larger market. Beyond the enthusiasts willing to pay $300 or $200 for a camera, there is a much larger market who would love to get great photos and videos while underwater or doing sports... but will not pay $300 to do it. The teenagers playing basketball in the local court, the kids riding their bikes around the neighbourhood, the family splashing in the pool, they all are a potential market, orders of magnitude larger than the enthusiasts, and they are unserved by GoPro. Eventually, someone manufactures a "good-enough" camera for them, then moves upmarket. GoPro needed to address that market as well. It might try to avoid brand dilution by doing it with a subsidiary, the same way that Toyota went upmarket with Lexus as a separate brand, but it needed to capture that market or lose it.

Summary

Could GoPro have prevented its current problems? Assuming the market to be big enough to sustain growth - and that is a big assumption - then, yes, they could have, by one or more of:

- Leveraging their cameras into a platform

- Creating additional value via "positive lock-in"

- Cannibalizing themselves via reducing prices to prevent high-end competition

- Attacking the vastly larger low-end market themselves

Good luck to them.